Luísa Margarida Portugal de Barros, the Countess of Barral, was the tutor to princesses Isabel and Leopoldina and was very influential in her position, and also a close friend of Emperor Pedro II.

Early Life

Luísa was born on April 13, 1816. Her parents were Domingos Borges de Barros and Maria do Carmo Gouveia Portugal. The father played the role of politician and then diplomat. In this position, he worked for the recognition of Brazil’s independence in France, and for that reason received the title of Baron of Pedra Branca. In addition, he had already had all his higher education in Europe, in Portugal – and was also a poet, one of the precursors of romanticism in Bahia. At age 35 he married Maria do Carmo de Gouvea Portugal, who was 19 years old and was already a widow. Luísa had a younger brother, also called Domingos, who was a child in fragile health. Furthermore, Domingos Borges de Barros had a son before marriage, who was considered illegitimate and whose name was Alexandre. He will be part of Luísa’s life more in adolescence and then they will have financial disputes.

For us to understand the context and social position of this family, it’s important to know that the children, Luísa and Domingos, were “breastfed by good slaves”. They grew up on the Bahian plantations, which were owned by the family. They were educated at home, by their mother, using books and booklets on literacy and religion. Their father was also involved in this education, mainly conveying a taste for letters, diplomacy, economics.

As Domingos worked as a diplomat, the whole family moved to France when Luísa was still a child. But in early 1825, his son Domingos became ill and died in February at the age of 10. The family was very affected by this, devastated by pain and there is a painting done right after that, it shows the serious and saddened family and a bust of little Domingos.

And as these things were, even more so with families with more financial means, Luísa had been betrothed at age 12 to a friend of her father, the Brazilian diplomat Marquês de Abrantes, 20 years her senior.

When she was fifteen, her mother got pregnant again, hoping to fill that void left by her son, perhaps. But what was supposed to be an occasion for joy has turned into a tragedy. The birth was complicated, and mother and son died in 1831. You can imagine that, after losing two children and his wife in Paris, Domingos no longer wanted to stay in the city. So he decides to leave with his daughter and a ruler to Boulogne-sur-mer, still in France. The plan was for Luísa to finish her education in France and then return to Brazil to get married. In the meantime, Domingos returned to Brazil to occupy his post in the senate and left Luísa in the care of a friendly family.

On this trip to Brazil, Domingos met Luísa’s future husband, the then Viscount of Barral. In the two months it took to complete the trip, they become acquainted enough that, when Barral returned to France, he looked for his friend Domingos – but instead of finding him, he met Luiza and fell in love.

Then in 1836 Luiza and Eugene became engaged and got married in April 1837, with Luísa having made her choice of husband prevail.

Luísa before her marriage

Eugene

Plantations and Maid of Honour

After that, the couple goes to Brazil. Visconde do Barral, who was a diplomat at the time, resigned to accompany his wife and help take care of the plantations in Brazil. They stayed there for some time, working and taking care of the mill.

In Del Priory’s biography, she tells of Luisa’s relationship with the plantation’s captives:

“Luísa taught ballet to the black girls. She liked to watch the slaves’ children bathe in the river and watch them dance the lundu. She also enjoyed having tea with Cacumbo or visiting Josefa’s newborn son.”

But she also said:

“Despite defending the end of slavery, Luísa valued discipline. She also handed out punishments or had a disobedient slave put in the stocks. This paradox was common. Since Abolition had not been decreed, even those who fought for it dealt with slavery, without concessions: “Twelve cakes to Maria da Assunção, who was drunk yesterday, and Henriqueta, for stealing corn.” Repeated thieves went to the trunk: “They stole the ducks and the castor oil: Ignorance whipped 15 times.” Her authority had to be respected. […] Heavy conscience? None. Punishment was part of the relationship between masters and slaves. For her, distributing cakes was a way to educate morally. […]”

One thing that some authors emphasize is that after her husband died, the countess gave orders that the children of her slaves were to be considered free, four years before the enactment of the “Free Womb Law” in Brazil.

The nostalgia for France was beginning to tighten, partly also because the financial situation was not so good. And then, in 1843, Luiza entered the life of the imperial family for the first time. Princess Francisca de Bragança, Pedro II’s younger sister, married the French Prince of Joinville, the third son of King Luís Felipe. Francisca, who had been educated in Rio de Janeiro, with no command of French and never having experienced a European court, needed a bridesmaid, a woman who would help her navigate that whole new world. The chosen one was Luísa, who was fluent in French and of course Portuguese, and already full of interesting connections. She was, at that point, known as the Viscountess of Barral, and she was appointed by the King of France as the Maid of Honor of Francisca, with the right to share the table with the royal family.

During this period, Luísa’s life was very busy, with various parties and court balls. The relationship with Viscount of Barral also seemed to be going well, without fights as they had in Brazil.

At the same time, Luísa opens a tearoom at her residence on Rua D’ Anjou, Paris, a space on her own property, where intellectuals, artists, politicians, gathered, talked and socialized. One of Luísa’s most famous paintings was done by the Winterhalter brothers, friends who frequented her literary and artistic salon in Paris, and who painted European royalty. One of the most distinguished names that frequented the salon was Chopin.

Five years later, in 1848, King Luiz Filipe was deposed and the family of Orleans took refuge in England. The king had abdicated in favour of his grandson Philip of Orléans, Count of Paris, but he was not recognized as a successor by the revolutionaries and, in the same year, they proclaimed the II Republic of France (1848-1852). During this time, Luis Napoleon, later called Emperor Napoleon III, was accumulating more powers. With that, the situation of the Barrals became more and more difficult, because Eugene’s family was related to Luis Napoleon, but they were friends of the Orleans. The ex-royal family’s money was tight. So then she decided to return to Brazil.

Once in Brazil, Luísa had a child, 16 years after her marriage, when she was 38 years old, which was not so common at the time for her first child. They say that it was a great frustration for her not to have children. In her diary, she commented on this fear of not having a child and how she had often lost hope, “due to my antics on foot or on horseback and dancing like a madwoman I was.”

Their son, Horace Dominique, was born in February 1854.

A few months after the birth of Dominque, a cholera epidemic hit Bahia. At the time, Luísa was still in town, since giving birth, and friends asked her to leave town and take refuge with her baby, her father and her husband in the country. Then she says:

“I was on my way to the mill when I learned of the precarious state of the orphans, which fear and chance condemned to abandonment and undoubtedly to death.”

She immediately chose to stay and help them, claiming that she was immune from God’s punishment because she was doing a good deed. She personally coordinated the orphanage of Providence until it was delegated to the Sisters of St. Vincent de Paula.

In March 1855, Domingos Borges de Barros had a worsening of his health, already suffering from liver problems, and died. Luiza stayed in the country for a while longer, taking care of the mills, but she was already planning to return to France. That’s when she got an important letter.

Tutorship years

At the Brazilian court, Princess Isabel had been recognized as the successor of Pedro II, at the age of four, after the death of her last brother. Therefore, the education of Isabel and Leopoldina became a priority. After all, they would be the future rulers of Brazil. Besides, it was necessary to prepare them for a marriage with foreign princes, accustomed to certain rules and etiquettes and requirements. As Pedro II’s sister, Francisca, said in a letter to him: “I think you are right to give your eldest daughter a man’s education, especially as she is likely to come to govern the country”.

Pedro II was then looking for a European preceptor, from countries considered to be models of civilization, to educate his daughters. It was difficult to satisfy Pedro II’s demands until, in 1856, his sister Francisca wrote about her former bridesmaid, Viscountess of Barral, who now lived in Bahia:

“My dear brother Pedro… I think you couldn’t choose better than Barral which is not only very well educated but also solid manners and principles in everything. She speaks French, English and her language perfectly well. The piano is also very strong. She plays perfectly well. And I believe that with masters under her sight and direction, everything can go as you wish and have an excellent education for your daughters. […]. What I fear is that Barral will not accept the position with her husband and especially her little son, who she herself never leaves alone.”

Once Luísa received the first official invitation for the position, she started to negotiate. She wanted to know all the conditions. Luísa made it clear that she was married and had children, which was not what Pedro II was looking for. That’s why she couldn’t live in Paço de São Cristóvão, and she needed a furnished house and car for transport. If there were emergencies in the plantations, her properties, she would have to go take care of those issues. She wanted to know what her position at court would be, what kind of treatment she would have. Who would be her right-hand woman, the person who would be responsible for educating and caring for the princesses when Luísa was not there? After many exchanged letters, at a certain point, Pedro II himself answered her questions.

Apparently, she was happy with the results achieved because she accepted the position. She would be given carte blanche to take care of and decide everything that concerned the upbringing of the princesses. Her food, carriage for transport, and Dominique’s education would be paid for by the emperor. The princesses would have professors for the various subjects, but she could teach whatever classes she wanted following the professors’ methods.

During this two-month period of negotiation, Luísa’s father-in-law died, giving Eugene the title of Count of Barral and she became the Countess of Barral. On August 31, 1856, she was then named Lady of the Palace, officially becoming the governess of the Brazilian imperial princesses. She will remain in that position for 8 years, from when Isabel was 10 years old and Leopoldina was 9, until the princesses’ wedding.

Part of Luiza’s job was to choose the masters who taught the different subjects. She also had to take care of their behavior, educating them about good manners and hygiene habits. She also wrote constantly to the emperors to tell about their daily life and activities.

The girls’ studies started at 7 am and went on until 9:30 pm, with breaks for meals and perhaps scheduled visits. They studied Calligraphy, Geography, Portuguese, Literature, Latin, Music, French, Mathematics, English, Embroidery, Sewing and Painting, Dance, Physics, Astronomy, History, Rhetoric, Poetry, Botanics, Mythology…

It is told that the Countess felt that the books and manuals available for teaching the history of Brazil and Portugal were insufficient. So she decided to write a manual herself. On the first day she was going to teach history, the Emperor arrived to attend the lesson too. About this, she wrote: “It is quite true that the next day when it was the Emperor’s turn to teach the lesson, he was more emotional and intimidated than I had been. This gave me, for the future, greater security”.

After a certain point, we begin to see the outlines of the friendship that develops between the Countess and Pedro II, and how he gives weight to what she has to say. In 1858, the Emperor travelled to the Northeast. On that occasion, Luísa created a kind of map of influential people that he was worth knowing.

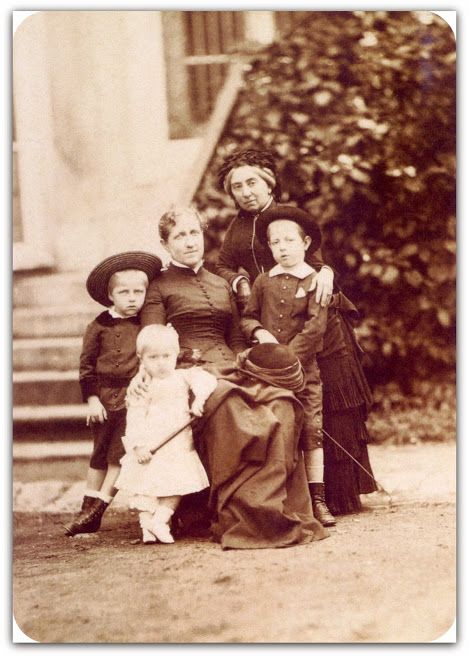

The princesses also developed a very close relationship with Luísa. She was always present, whether in everyday life or in letters when she had to be away. So much so that even after Isabel’s wedding, the princess still constantly sought out Luísa’s advice. The Countess even helped arrange the weddings, according to historians at the time. In the end, she and Isabel remained very close throughout their lives, with several photos of Luísa with Isabel’s eldest son existing, and letters being exchanged between the two.

Luísa, Isabel, and children

Luísa and Isabel’s son

After fulfilling her contract to educate the princesses and after their marriages, Luiza retired, receiving the title of Countess of Pedra Branca but denying the life pension that had been agreed upon.

Pedro II and Luísa: Relationship rumours

In the 1950s, Pedro II’s letters to the Countess were discovered, wrapped in a little purple ribbon. These letters gave rise to several books transcribing the letters, weaving comments and creating a whole narrative. Some of them spoke of their relationship, while others really passionately defended that Pedro II never had lovers.

But this story of the romance is not just a 1950s construction, looking back at the past. Back in the 1880s, newspapers were already talking and speculating about Pedro II’s private life and their possible relationship.

Historians are not unanimous in saying whether there was an extramarital relationship or whether it was a platonic friendship, with loving feelings but without going further.

What we do know is that there are many letters exchanged between them for 20 years out of the 40 years of their friendship. We also know that many of them were burned by Pedro II, because he mentions that they had this pact in one of the letters. The fact is that they had an intimate relationship, talking openly by letter about mundane and important things.

After Luísa retired, she returned with her husband and son to France, in 1865. There, she reopens her literary salon, returning to relate to those known to French cultural life. Shortly thereafter, in 1868, the Count of Barral died.

After her husband’s death, we have some letters from the Emperor in which he asks her to consider living in Brazil. But she didn’t come back. During this period, from a year before the Count’s death until 1874, the letters show the construction of this friendship around the things they had in common: the love of literature and the arts, friends or acquaintances, travels, Dominique’s education. She sent books and literary news from Europe to Pedro II. They also talked about money, politics, cultural discussions, their health, joys and sorrows.

As we said before, the press talked about this relationship, sometimes in a veiled way and sometimes explicitly. There were cartoons and comics that became popular, saying “Where are your virtues, Oh monarch? It is certainly not good morals, cheating on one’s wife with Barral”. It was a time of great tension between republicans and monarchists. Luísa became, in a way, a target to reach the monarchy and the figure of the Emperor, being appointed as a mistress.

Luísa stayed in Europe and witnessed the various political and social upheavals that took place in France. In 1871, Leopoldina died at the age of 25, of typhoid fever. The Countess wrote desolately to the emperors and then sent yet another letter just to the Empress. I think this shows that, despite what they say about the rivalry that existed between them, Luísa always took care so that the Empress did not feel rejected.

Some of the last photos of the Countess of Barral

Some of the last photos of the Countess of Barral

That same year, in 1871, the Emperors made a trip to Europe, and Luiza, of course, accompanied them. About the reunion, Luísa wrote that Pedro gave her a hug in front of everyone, and wrote how he was aged but with a happy countenance. But, at least in Mary del Priory’s biography, this trip seems to have been full of disagreements. She found his habits and etiquette too “hill billy” for European courts, his manner too ugly. She didn’t like the way he treated the Empress, who had just lost a daughter. She wrote in her diary:

“Jesus Mary, who created him so selfish! My God! Nice way to travel for his wife’s health! Poor thing must be his humble slave, he doesn’t allow the slightest reflection, he never gives in to anything […] woe to anyone who doesn’t say Amen to everything he wants. […] It becomes unbearable and rude! And as I am such a big fool to love him and to desire everything that is for his good, it is on me that he discharges his bile. And then he comes and says a dozen kind words to me”.

From 1880 onwards, they began exchanging diaries: one wrote about their day, thoughts, events – sent to the other, who made comments and added his diary and sent it back. In one occasion, Luísa gets annoyed and writes: “It’s so rare for you to tell something else that ‘I took a shower, saw my grandchildren, read, had coffee’. Without any censorship, I wouldn’t call it talking to an old friend.”

And we can also see the affection between them, when Pedro II’s writes: ““I’m very tired and I would throw myself in bed if the longing didn’t demand that I give you the most affectionate good nights. Goodbye, dear friend! Nothing interests me completely apart from you. Goodbye!”

In 1883, Luiza returns to Brazil for the last time, for the wedding of her son Dominique with Chiquinha Paranaguá, the sister of one of Isabel’s close friends.

This event was a trigger for the attacks on Pedro II and the royal family, as they appeared at the wedding, contrary to the rules of court etiquette. In the newspapers, it was said that the emperor could not have “expansions disagreeing with all his previous acts.” That the emperor’s position obliged him to “not appear more devoted to his private friends than to the friends of the nation, those who had served at the same time his person, the existing institutions and the country.”

A few years later, in 1889, the monarchy fell. As a result, the Imperial family went into exile and spent some time at Luísa’s house, in Voiron. Even the most famous photos from that period were taken there. A short time later, the Empress died on December 28, 1889.

On January 14, 1891, Luísa dies. It seems that it was quite sudden; she started to complain of cold, came a fever, weakness, vomiting, she lost her vision. But she still had the strength to say how she wanted the altar, the candles and everything else arranged. They say her last words were “I’m tired, let me sleep.” On December 5 of the same year, the former Emperor died.

More information (in Portuguese):

- Biography by Mary Del Priori:

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/9424000-condessa-de-barral - https://periodicos.pucpr.br/index.php/dialogoeducacional/article/view/27445

- https://seer.ufrgs.br/asphe/article/view/77091

- http://www.congressohistoriajatai.org/2016/resources/anais/6/1475510314_ARQUIVO_JataiTEXTO.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326661698_Um_olhar_critico_sobre_a_figura_da_condessa_de_Barral_na_biografia_historica