Today we are not going to talk about one woman… or two… but three women!

These women have several things in common. Among them, the fact that we do not have much factual information, since it is difficult to separate myth from fiction. Another thing in common: these three women lived in the 16th century. And a third point in common: they were all called “the mother of Brazil” or “the mother of Brazilians”. But in a very different way than Ana Nery, who was called that too.

These three women are: Paraguaçu, Bartira and Muira.

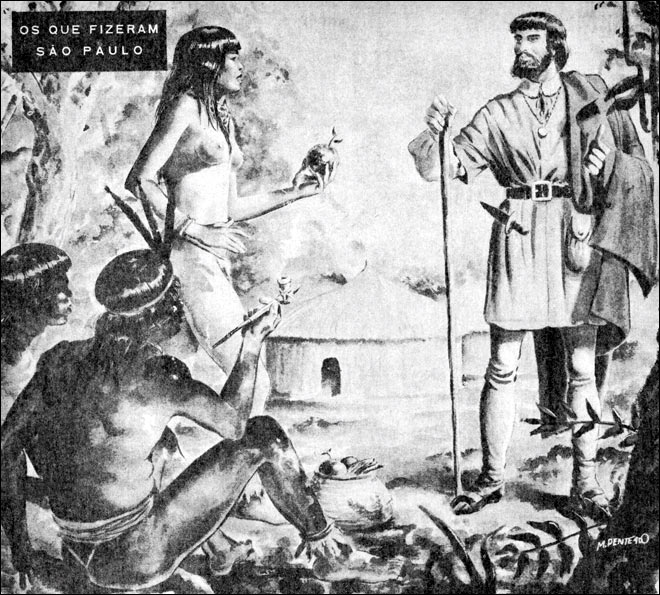

Literature will play a very important role in the history of Paraguaçu. That’s because so much has been written and romanticized about it. So today I will try to bring the real history of Paraguaçu – and, consequently, of Caramuru. And, of course, I will talk about the myth that literature has built up. Speaking of Caramuru, this is another point in common among our women. We have records of them for one main reason: they married Portuguese, at the beginning of Portuguese colonization. They were, in fact, three of the first indigenous people who were involved with Portuguese people, as far as we know. Much of what was written about them is from this perspective of their union: not so much as individuals, or women – but as wives of these men.

Paraguaçu

According to her christening certificate, Paraguaçu was born in 1503. She was the daughter of a great warrior and Tupinambá chief named Taparicá. In fact, it is said that her name when she was born was Guaibimpará, Paraguacu being a name that was given to her years after her death, perhaps because of the region in which they lived.

In 1509 or 1510, Diogo Álvares, a Portuguese shipwreck who was probably on board a French ship, arrived on the coast of Bahia. He was probably 17 years old. The most romanticized version of the story said that he was called Caramuru by the indigenous Tupinambás in the region, because he fired the weapon he had. That noise, like nothing the natives had heard, was the reason why he was nicknamed “the son of thunder”. But the truth is better, I think: he was found with his clothes soaked and glued to his body, in the middle of the stones, looking like a moray eel, hence the name Caramuru.

And why would her father do that? According to the book Mulheres do Brasil, by Paulo Rezzutti:

“It is important to note that this was one of the first unions between Portuguese and Indians to consolidate a kind of political alliance through kinship. This first couple would also serve as an example of acculturation for Brazilians ”.

In other words, he could have seen an ally in Caramuru, since whites were already arriving at the Brazilian coast.

Historian Mary del Priore also talks about marriages in the indigenous context as a form of diplomacy:

“In the tribal tradition, the only way to relate peacefully to strangers was to integrate them into a family relationship. This occurred through marriage to one of the women in the village, making white a brother-in-law or son-in-law. And in the future, an uncle, a father and a grandfather. Such a marriage strategy was not a European creation. It was a fortuitous agreement. It worked as a way of organizing the transition from collective production to that of regular surpluses or the provision of services, such as the repair of ships in exchange for iron instruments and trinkets. Alliance weddings took the same form with all European peoples who maintained contact in the Tupi-Guarani area.”

Whatever the reason, they got married. Of course, not a European, Christian wedding. For all I read, polygamy was the norm in the culture that Caramuru and Paraguaçu were in, and Caramuru had children with several other women. But there’s a hint of romanticism in that story too: they stayed together for the rest of their lives.

When the first Portuguese civil authorities arrived in Bahia, as well as the first Jesuits and the many European vessels, Diogo helped by providing important information about the land and the people, acting as an interpreter and mediator. He built relationships, mainly with the French.

In 1524, Jaques Cartier took Caramuru and Paraguaçu in his vessel, to France, specifically to Saint-Malo. There, Paraguaçu was christened Catherine du Brésil, possibly in honour of Catherine des Granches, wife of Jacques Cartier, who was his godmother. There, too, they got married, on July 30, 1524. And the coolest thing is that these documents exist and were found in 1931, in Canada.

Despite being named Catherine du Brésil, she was better known as Catarina Álvares Paraguaçu. In 1531 the couple was back in Bahia, living where today is the city of Salvador. They also played an important role in the alliances between Tupinambás and the Portuguese.

In 1536, the Portuguese Francisco Pereira Coutinho appears with a letter from the king of Portugal designating him Lord of the lands there. Later, Caramuru receives a piece of land and is recognized as an ally to support the installation of the government-general. Thus, Tomé de Souza comes here already instructed to maintain good relations with the Caramuru family. The sons even have positions of command in the government organization and Catarina sees to it that the daughters have good marriages.

The Álvares family started to have a certain importance, then. One of the daughters, Madalena Álvares or Madalena Caramuru, had more prominence. Some historians, like Gastão Penalva and Francisco Varnhagen, say that she was the first Brazilian woman to know how to read and write. In 1534, she married Afonso Rodrigues, a Portuguese. She was known for reporting violence against the native indigenous and proposing the creation of a school for children. She even wrote a letter addressed to Father Manoel da Nóbrega, asking that enslaved indigenous children, “without knowing God, without speaking our language and reduced to skeletons”, should be treated with dignity. What is said is that the priest was moved by the request and interceded with the Crown asking for permission to create schools for indigenous children. But Queen Catarina de Bragança denied it. humans. In 2001, the Post Office put Madalena Caramuru on a stamp of R$ 0.55.

In 1557, with the death of Caramuru, Catarina inherited not only the money they had accumulated, but also power. After all, they have become important figures since the establishment of a colonial government organization. She would then have taken care of the family business, promoting advantageous marriages for sons and daughters and financing social works and in the foundation of the Igreja da Graça. She had really become very religious, and she founded one of the first churches in Brazil. Catarina was the first indigenous woman really devoted to Maria in Brazil, at least as far as we know.

When she died, on January 26, 1583, her assets were donated to the Monastery of São Bento da Bahia. Her remains were buried in the Abbey of Nossa Senhora da Graça, in Salvador.

Now we are going to skip a little time, to 1680, that is, a century after Paraguaçu’s death. This was the year that Jesuit Simão de Vasconcellos wrote about the life of Caramuru and Paraguaçu, adding some elements of legend to the story.

Telling about the trip from Paraguaçu and Caramuru to France, he says that she was received with great curiosity in Saint-Malo. She was baptized Catarina, or Catherine du Brésil, becoming “a true Christian lady”. The couple returned to Brazil with two loaded ships and artillery, after committing to fill the French ships with redwood, which they did.

Some time later, he says that a shipwreck of a Castilian ship took place, in which Diogo helped rescue the survivors nearby. Catarina asked Diogo “to look for a woman again, who had come in the ship, and was among the Indians, because she appeared to him in vision, and told him to send her to come to him and make him a house”. After many attempts, “an image of Our Lady that an Indian had collected on the beach and had thrown in the corner of a house” was found; Catarina identified this image with that of vision; the image received a house and was “honored with the title of Nossa Senhora da Graça, enriched with many relics and indulgences. He goes on to say that “the sons and daughters of these two devotees of the Lady were baptized by religious, marrying several daughters with noblemen and from this union came many of the best and most noble families in Bahia”.

Already inspired by these writings, in 1781 Frei José de Santa Rita Durão wrote the epic poem Caramuru, in Coimbra. Then he added the whole idea that Caramuru meant son of thunder. In the poem, Paraguaçu is an indigenous woman with white skin, European features, speaks Portuguese. And, of course, they fall in love at first sight. Other characters appear: Caeté, who loves Paraguaçu. And of course, the famous Moema, the most beautiful of the Indians who fell in love with Caramuru.

In the poem, on her return to Brazil, Catarina Paraguaçu prophesies the future of no and all future conflicts. And of course, super devout.

Moema is an interesting character. In some articles, they say that Moema existed, and was one of the women offered to Diogo Alvares. Others even say that she was the sister of the Paraguacu. But she is really known as the character in the epic poem and the painting by Victor Meirelles, from 1886, inspired by the poem.

Moema appears for the first time in corner VI, when Caramuru decides to go to France with Paraguaçu. «It was no less beautiful than angry», with envy, speaking ill of Paraguaçu (she calls her «unworthy», «infamous», «traitor» and sees «inferior», «foolish» and «ugly»).

In the poem, Moema wouldn’t mind going after Caramuru – but she would have to be subordinate to Paraguaçu, which she doesn’t accept. When he leaves for Europe with Paraguaçu, Moema swims, grabs the helm and begs for Diogo’s love. She passes out and drowns, also representing the other indigenous women who went after Caramuru. She is the opposite of Paraguaçu: while Paraguacu is pious and covers nudity, Moema swims after her love and is always nude. Victor Meirelles’ painting shows her body on the beach, after sipping the water. In the 19th century, poetic anthologies and literary stories focused much more on this tragic character and on this part of the “death of Moema”.

So as we see, the history of Paraguaçu and Caramuru has been built and reconstructed in the oral tradition. And much of what we have really gives a focus to Caramuru, and much of Paraguaçu’s real legacy has been forgotten. Jorge Caldeira, in the book 101 Brazilians who made history (2016), said something that I think is pertinent:

“Until the Tupinambá ways of being were studied, the essential role of native women in building a new society was erased from history.”

Bartira

To speak of Batira, I relied heavily on the book by Jerome Adams, translated title is notable women from Latin America and also on the Brazilian Women Dictionary. He calls Bartira and Paraguaçu mothers of Brazil, mothers of the nation, for being the first indigenous women to be registered, who had relationships with Portuguese people. He explains that historians of the 16th century called both Bartira and Paraguaçu princesses, because that was the closest to the Eurocentric conceptions that they had. But, as we have already seen, they were daughters of tribal chiefs.

And then, he talks about an interesting distinction that the journalist and writer Clodomir Vianna Moog made, which I find super interesting, is that the relations between the colonizers and the native women in Brazil were very different from those that happened in North America. The Portuguese, saw women as object of prey. Puritans who immigrated to the United States, products of church reform, saw women as a companion in work. While the Americans preferred to bring Puritan women of the same origin, the Portuguese took women, inside or outside marriage circumstances. This is an interesting thing to keep in mind when we think about the relationships that were starting at that time.

Bartira’s indigenous name was M´bicy (Flôr de Árvore). Like Paraguaçu, she was offered by her father as a wife to a Portuguese in the early 16th century. That Portuguese was João Ramalho.

The story goes that Tibyriçá, the head of a group of indigenous Guaianases, felt sorry for or sympathized with João Ramalho. We don’t know how he arrived in Brazil: maybe as a victim of a shipwreck, maybe a criminal sent to serve his sentence in Brazil, or maybe he volunteered to come and colonize the land. The region in which they were located was the future captaincy of São Vicente (a captaincy that passed through Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais and São Paulo).

João Ramalho was the first European to climb the mountain, called Paranapiacaba (“a place where you can see the sea”) where he established contact and was welcomed by the indigenous people, mainly Tibiriça (“guardian of the land”, in the Tupi language). With the wedding of Bartira and Ramalho, a bilateral alliance was created, which, as we have seen, gave a certain prestige to the European within indigenous structures. It is said that Another daughter from Tibiriça, Terebe, was also married to a Portuguese.

Bartira and João had 4, or 5 children, and lived together for 40 years. João Ramalho also had children with many other women, since polygamy was part of the culture.

In 1532 there was a meeting between Ramalho and later Baritra, with the other Portuguese. He learned of the arrival of a Portuguese expedition on the coast and went along with another Portuguese, Antonio Rodrigues (who was married to a daughter of Piquerobi, brother of Tibiriçá), to meet the newly-arrived – and perhaps offer their services by navigating relations with local indigenous people, translating, etc.

When the first Portuguese colony was founded in 1532, Jesuit priest Manoel de Nóbrega was frightened by the habits of the Portuguese and, on June 15, 1553, this is how he referred in a letter addressed to Father Luís Gonçalves da Câmara: “In this land is a man called João Ramalho. His whole life and that of his children is according to that of the Indians and is a petra scandali for us, because his life is the main hindrance we have, because he is very well known and very related with the Indians. He has many women. (…) They go to war with the Indians and their parties are of Indians and so they live walking naked like the same Indians” (Leite, 1940, p. 46).

Ramalho helped the Portuguese, often acting as a bridge. After all, there were 5 language groups in Brazil, with 2,000 dialects. The Tupis on the coast, the Tupayas, who spoke GPE, the Arawaks and the Caribs, and the Guaycurús.

It was in conversations with that Father Manoel da Nóbrega that João Ramalho let it slip that he was already a man in Portugal, with a woman named Catarina Fernandes das Vacas. He hadn’t seen or heard from her since she left Portugal, nor did he know if she was still alive. But the fact is, he was married in the church. He was then excommunicated. A version of the story tells that Nóbrega wrote to Portugal to find out about Catarina’s existence – I don’t know what the verdict was, but in the end he held João Ramalho’s wedding with Bartira, after they had been living together for forty years. She was baptized as Isabel Dias and converted to Catholicism. But in the Dicionário Mulheres do Brasil, the authors say that there is no documentary record of legal marriage between them. And one thing that corroborates this version, is that in João Ramalho’s 1580 testament, Bartira (now Isabel) was mentioned as his maid, and not as wife. It is presumed that because he was still legally married in Portugal.

The sons and descendants of Bartira and João Ramalho populated the Piratininga plateau, with the couple in charge. Some of the couple’s children had prominent unions: Joana Ramalho married a captain of the Captaincy of São Vicente, who ruled for 7 years.

Muira Ubi

And to close, we also have the story of Maria do Espírito Santo Arco-Verde. We know much less about her, only that she is also the daughter of the Tabajara chief Uirá Ubi, from the indigenous nation that dominated the Pernambuco coast. Her name was Muira Ubi, before her baptism. Nicknamed the “Princess of the Arco-Verde”, it is said that she was wonderful with the bow and arrow. How cool is that?!

In the mid-1530s, a military chief disembarked on the coast of Pernambuco, named Jerônimo de Albuquerque. He became a prisoner of the tribe and sentenced to death along with other Portuguese. The story that is told is that Muira Ubi interceded for him, saving his life. They then got married and she was baptized on Pentecost Sunday, which is when the holy spirit appears to the apostles, which explains her new name Maria do Espírito Santo Arco-Verde. For a while, things calmed down, the Portuguese and Indigenous on the coast were in relative peace. The couple had eight children together, one of whom married a Florentine and formed an influential family: Cavalcanti de Albuquerque. Then, the queen of Portugal gave orders for Jerônimo to separate, since he had a noble ancestry and could not “follow the law of Moses and keep three hundred concubines”. He then married a noblewoman named Filipa de Melo.

Unfortunately, we don’t know many things about Muira Ubi – what we know about her life comes down to her relationship with Jeronimo.

In fact, this is an important thing that all the women we talked about today have in common. These women that we have records were visible for their role considered important from the point of view of interaction with the colonizers. These men lived among the Indians, but they also rendered their services to the colonizers, helping with the task of colonizing the region. Is that a good role, a bad one? I don’t think there is an answer to that. On the one hand, we can argue that they avoided bloody conflicts by acting as mediators. But on the other, we know the result of that and the destruction it has brought. I wonder, do we have the stories of Europeans who took on the culture of the tribes that welcomed them and refused to help the Portuguese? Who wanted to defend indigenous culture instead of introducing European culture?

It is good to remember that, despite these three stories, not all indigenous women followed this path, but we don’t have a lot of information about their lives. As it is in the book Dicionário Mulheres do Brasil: “A few indigenous women emerged as warriors fighting against whites, like Ingaí, a caeté who lived on the coast of Pernambuco and would have died in 1535. She fought bravely with her tribe against the colonizers. She ended up being imprisoned after the death of her betrothed.”

I hope that this episode has done at least a little justice to the lives of these women and that it also arouses the desire to learn more about the struggle of indigenous women today. Women like Azelene Kaingang, Founder and member of the National Commission for Indigenous Women of the Brazilian Indigenous Institute; Joênia Wapichana the first indigenous woman to exercise law in Brazil; Kerexu Yxapyry Eunice Antunes, who fights for the demarcation of indigenous lands and many, many others.

More information (in Portuguese):

- Notable Latin American Women: https://books.google.be/books/about/Notable_Latin_American_Women.html?id=jCNz6CoIZV4C&redir_esc=y

- 43 indigenous women we should know: https://catarinas.info/43-mulheres-indigenas-do-brasil-e-da-america-latina-para-se-inspirar/

- Dicionário Mulheres do Brasil: https://books.google.be/books?id=83DTDwAAQBAJ