Ana Néri (a.k.a. Anna Nery) is known to every nurse from all over Brazil, and do you know why? That’s because she is our country’s first nurse, or at least she’s acknowledged as the first one.

The main document for our research is the article “Ana Justina Ferreira Néri: um marco na história da enfermagem brasileira” by Maria Manuela Vila Nova Cardoso and Cristina Maria Loyola Miranda, published in 1999 in the Brazilian Journal of Nursing.

Early Life and Marriage

Ana Néri, also known as “Mother of Brazilians”, was born Ana Justina Ferreira on December 13th, 1814 at Vila de Nossa Senhora do Rosário do Porto de Cachoeira. Cachoeria is a county from Bahia, near Paraguaçu river, and it’s a very important city for Bahia’s tourist circuit.

The street where she was born, Rua da Matriz, was renamed in August 1926 as Ana Néri Stret. We don’t have any information about her parents, aside from their names: José Ferreira de Souza and Luiza Maria das Virgens. What we do know is that Ana’s four brothers all had social prestige. Two of them were lieutenant colonels and led battalions of volunteers – we’re going to talk about them later. Another brother was a general practitioner and the last one was a broker, so is noticeable her family had a high social status. Especially considering medicine was an upper-middle-class career even back then.

The men in her circle and family had prestigious professions – meanwhile, the women were being prepared to serve their future husbands, raise their children and take care of the house. And this is what we can infer about Ana’s life since we don’t have information about her childhood or youth. As it happened often, the woman’s life isn’t acknowledged until her marriage. Even so, there are reasons to believe Ana was educated for marriage. In her case, this occurred actually a bit later than usual at the time, since Brazilian women usually got married between 16 and 20 years old and she got married only at 23.

In 1838 she married the marine lieutenant-colonel Isidoro Antônio Néri, a 37 years old man born in Lisboa. Fourteen years older. At that time, it wasn’t quite a big difference. She took his last name, being now known as Ana Néri, and becomes a housewife. Yet her marriage had a particularity. Because of his professional role, Isidoro Antonio was often away from home, therefore she was usually alone with their children, taking care of the household on her own.

Antonio returned home for short periods, and in approximately 3 years they had three sons. The first son was born in February 1939, nine months after the marriage. Six years after their marriage, Isidoro Antonio died at 44 years old, from sudden illness aboard his ship. There is no further information about his illness, but Ana became a widow at the age of 29 and her children were 5, 3 and 2 years old. She had a lot of responsibilities all by herself, although since her late husband was barely home before, she was probably already used to dealing with those responsibilities.

Eventually, the family moves to Salvador, probably after the children finished high school so that they could continue their education and have opportunities to go up in the social ladder.

In Maria Manuela Cardoso’s article, there’s an interesting description of the role widows should play on the society:

“The widow should live as the virgins, be alert to married women and give virtuous examples, being a friend of retreats and enemy of mundane fun. Be applied to prayers, care for her reputation, love mortification and work for God’s glory, in other words, sustain herself in Church obligations (Mattoso, 1992, p.411)”.

In the second half of the XIX century, Ana lived in Salvador with her two older sons, both studying medicine, while the younger one was a cadet in the Military Academy at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’s capital at the time.

Paraguayan War

Now we have to stop a bit and talk about the Paraguayan War. Here is the short version of it: the Paraguayan War, or War of the Triple Alliance, was fought from 1864 to 1870. Paraguay confronted Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay – the Triple Alliance.

At the time, there was a civil war between two political factions in Uruguay: the blancos and the colorados. In 1862, after his father’s death, Solano López took the lead as Paraguay’s dictator and got close to the blancos. The blancos were on the same side as Uruguay’s president Bernardo Berro, and the Paraguayans wanted access to Mondevideu seaport since they had no access to the sea.

It’s also important to know that the blancos were allies of the Argentinians federalists, thus they were enemies of the Argentinian government (supportive of the colorados). The policy of the colorados was similar to what Brazil needed: free trade and free navigation in the rivers of the region. Therefore, in 1863 the Brazilian government stepped in supporting the colorados in the Uruguayan civil war, using as an excuse the assaults some blancos supposedly made against Brazilian citizens in Uruguay.

Solano López, blancos’ ally, presented an ultimatum in August 1864 to Brazil: stop stepping in on Uruguayan internal matters. In September 1864, Brazilian troops invaded Uruguay supporting and enabling the colorados, to seize power with president Venancio Flores. Under the command of Solano López, Paraguay captured a Brazilian ship and invaded a region of Brazil in December.

As an answer to the Paraguayan invasion, Argentina also stepped in to aid the Uruguayan blancos, since the Argentinian president had denied free pass to Paraguayan soldiers. Solano López declared war against Argentina and then emerged the Triple Alliance, formalised in May 1865. Even so, the Triple Alliance troops didn’t add up to even half of the size of the Paraguayan forces. Brazil had less than 12 thousand trained soldiers. Hence, the Brazilian government created battalions of volunteers – the same ones we’ve mentioned before, talking about Ana’s brothers. At first, the volunteers would gain some benefits, such as financial prizes or freedom from slavery. Alongside the great patriotism sweeping the country at the time, it worked. But as time passed and the conflict dragged on, the provinces were ordered o meet quota requirements, recruiting at least 1% of the province’s population.

Mother of Brazilians

Now we can return to Ana. In 1865 she was 51 years old. Her sons were then recruited to war. In 8th August, she wrote a letter to the President of the Province of Bahia, offering to aid in the war effort, taking care of the wounded.

“Sir: – Having already marched into the army two of my children, as well as a brother and other relatives, and having offered the only one I had left in this city, a 6th-year medical student, to also follow the luck of his brothers and relatives in defence of the country, offering his medical services, – as a Brazilian, I cannot be indifferent to the sufferings of my countrymen, and, as a mother, I cannot resist the separation from people that are dear to me, and for such a long distance, I wished to accompany them everywhere, even in the theatre of war, if that were allowed to me, but opposing to my desire my position and my sex, they do not, however, prevent me from offering my services in any of the hospitals in Rio Grande do Sul, where they are needed, with which I will satisfy both the mother’s impulses and the duties of humanity towards those who sacrifice their lives for national honour and pride and integrity of the Empire.”

Lady Ana Justina Ferreira Néri

She talks about what is opposed to that desire: her position and her sex. And here, one thing to remember is that women had already been involved in that war. Not only supporting their countries, but also accompanying children, husbands, brothers. Other women accompanied the armies to serve as washerwomen, cooks and traded essential items. And it wasn’t uncommon for children to be born in the camps during the war.

This attitude was not uncommon, but one thing that distinguished Ana is that she was definitely part of an elite. And it is sad to realize that there are so few reports of Brazilian women in the Paraguayan war. And the one that we have the most access to, of course, was part of the elite.

One thing we don’t know was whether she had any experience with nursing before that. Some speculate about the possibility that Ana belonged to the Society of Ladies of Charity, which was founded in Salvador a little earlier. The women who were part of this society were of higher social status, and ended up having experience in charitable works.

But, on the other hand, the nursing profession did not exist. It was not rare for women who assisted doctors in this role to have no specific knowledge of nursing.

The response to Ana’s appeal was positive: the Commander-in-Chief of Arms was ordered to hire Ana as the first nurse. In the response of the provincial president, he talks about how she offered herself to “provide the services of humanity compatible with her sex and age”.

It is interesting to think about the speed with which her request was accepted: 5 days between sending the letter and receiving a positive response. It indicates that the authorities saw a chance there to use it as propaganda, to cheer people up: a high-class woman, asking to be allowed to go to war. So it makes sense that her letter was not only accepted but published in the newspapers.

Then, five days later, on August 13, 1865, Ana embarked for Rio Grande do Sul. She joined the 10th Battalion of Volunteers (Batalhão de Voluntários da Pátria) as a nurse. There she took nursing lessons and did an internship in Salto, Argentina.

In the book “Heroínas Bahianas” (1936) by Bernardino José de Souza, the author describes how Ana spent five years fighting alongside the army, fulfilling her “holy” mission of “warm sympathy and love for neighbour”. It was in this campaign, of course, that she received the nickname Mother of Brazilians.

According to Manuela Vila Nova, deputy director of the Ana Néri School of Nursing, at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Ana was responsible for the field hospital’s laundry first. “First she was in charge of the local laundry. Then she developed the concept of keeping clothes, work tools and work space clear. Beyond managing this sanitation, including of the hands as we see now, she cared about the people and also started taking care of them, changing dressings and committing to the nursing activities.”

Throughout the campaign, she worked in military hospitals and also on the operational fronts of various stages of the war, such as Salto, Corrientes (Argentina), Curupaiti, Humaitá, and Asunción (Paraguay). It was there, in Asunción, a city besieged by the Brazilian army, that she set up a model infirmary, with one of her children. She paid for it herself, with her inheritance money.

Much is said about her exemplary dedication and how she served everyone, regardless of nationality in the five years she remained at the front. The conditions, as you can imagine, were poor: without hygiene, without materials, surrounded by the suffering of thousands of wounded and dead soldiers. Of course, at that time most deaths were not caused even in battle, but from diseases: cholera, typhoid, dysentery, malaria, smallpox… they were all prevalent diseases. Some reports indicate that another important collaboration of Ana was to impose minimum conditions of hygiene, which was already essential to help not spread these diseases.

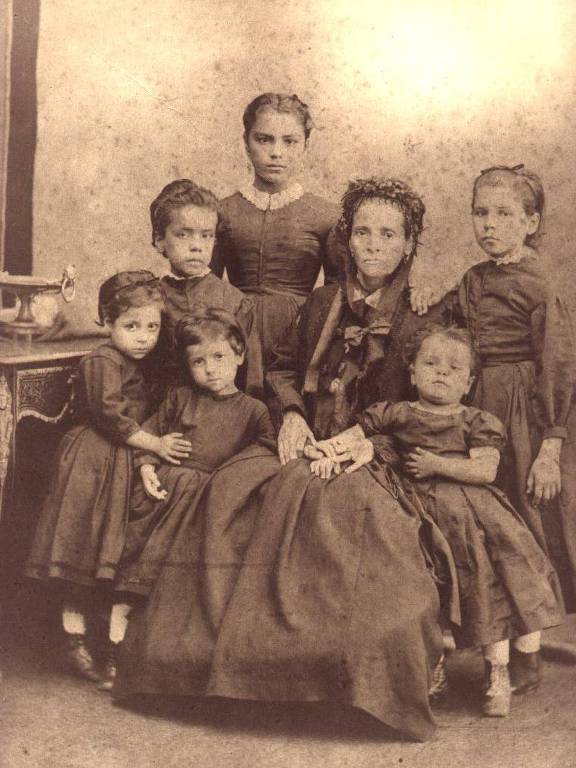

In the war, Ana lost her eldest son, Justianiano, a doctor, and also her nephew. Even after this son’s death, she did not return. With the end of the war, in 1870, she returned to Brazil. She also took 3 orphans (some sources say 6 children) from the war with you. In the field she had already received recognition and honours, but it was when she arrived in Rio de Janeiro that she received many of her honours and tributes. There, reports are that she was received by women from Bahia, who presented her with a mother-of-pearl and silver album, with the dedication: “Tribute of admiration to the charitable Ana by some compatriots”

It was also there that the most famous painting by Ana Néri was commissioned, in real size, to be offered to the province of Bahia. The painting was made by Victor Meirelles, and Ana appears with a laurel wreath and a medal on her right chest. She also received the campaign medal and an annual pension. The tributes continued in Bahia, where she was received by the illustrious family there, receiving a laurel wreath studded with diamonds.

Ana Néri moved to Rio de Janeiro, where one of her children served as an army captain. And it was there, where she died of pneumonia, on May 20, 1880, at the age of 65. She was buried in the São Francisco Xavier Cemetery, and her stonework has the inscription: Here rests the remains of Lady Ana Néri, called Mother of Brazilians, by the Army, in the campaign of Paraguay.

Today, her remains are in Cachoeira, the city where she was born.

In 1923, the first official Brazilian nursing school was named Ana Néri and in 2009, she joined the Book of Heroes of the Fatherland.

More information (in Portuguese):

- https://www.scielo.br/pdf/reben/v52n3/v52n3a03.pdf

- http://gmbahia.ufba.br/index.php/gmbahia/article/viewFile/981/959

- http://www.snh2011.anpuh.org/resources/anais/30/1405373398_ARQUIVO_Textoanpuhrs.pdf

- http://www.encontro.ms.anpuh.org/resources/anais/38/1412131987_ARQUIVO_HeroinasBahianas(1).pdf

- https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/equilibrioesaude/2020/05/Ana-Néri-grande-simbolo-da-enfermagem-brasileira-morreu-ha-120-anos.shtml